Melbourne, Australia (Tuesday, August 15, 2017, Gaudium Press) It’s confidential and considered sacred – a conversation strictly between a confessor and priest, never to be divulged. The secrecy of the confessional, a centuries-old sacrament, is taken so seriously that some priests would die before disclosing what has been shared.

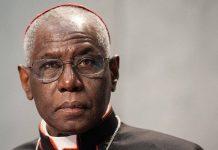

Archbishop Denis Hart of Melbourne, who as president of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference represents all Roman Catholic clergy in the country, said Tuesday that he would rather go to jail than breach the seal of confession.

“The laws in our country and in many other countries recognize the special nature of confession as part of the freedom of religion, which has to be respected,” Archbishop Hart told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

His comments came a day after religious institutions across the country were forced to defend the secrecy of confession after Australia’s Royal Commission Into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse recommended a sweep of legislative and policy changes, one of which would require priests who hear about sexual abuse in the confessional to report it to the authorities. The 85 recommendations were aimed at reforming Australia’s criminal justice system to provide a fairer response to sex-abuse victims, the commission said.

Advertisement

“There should be no excuse, protection nor privilege in relation to religious confessions,” the report said. “We heard evidence that perpetrators who confessed to sexually abusing children went on to reoffend and seek forgiveness again.”

Archbishop Hart responded on Tuesday, saying: “I think priests are men who are very carefully trained. Priests in my diocese in Melbourne are very conscious of the difficulties of the present situation.”

He continued, “We want to be faithful to God and faithful to our vows, but we do want to be responsible citizens, and we’re totally committed to that.”

Though the recommendation, made as part of the commission’s investigation into the church’s handling of sexual abuse allegations in recent decades, has drawn fierce opposition from the church authorities, it’s not the first time the issue has come up. In 2012, when the federal government announced the Royal Commission, the question of priests’ obligation to report any knowledge of child sex abuse to the police was already being discussed.

“Such an obligation would undoubtedly enhance protection of the rights of children,” Prof. Sarah Joseph, director at the Castan Center for Human Rights Law at Monash University in Melbourne, wrote in 2012. “It would also interfere with the freedom of religion of priests if they are compelled to reveal information conveyed during formal ‘confessions.'”

She continued, “In this clash of rights, which should prevail?”

It is not known what will become of the recommendation in the report on criminal justice, which was released just months before the commission is expected to publish its final report on its yearslong inquiry. But on Tuesday, Professor Joseph said legislative change was not out of the question.

“There’s a lot of sentiment on the side of the Royal Commission and a lot of disgust at a lot of the things that are being uncovered,” she said.

The Royal Commission examined abuse accusations in many of Australia’s religious institutions, including those associated with the Anglican Church, the Jehovah’s Witnesses and Orthodox Judaism. It concluded that 7 percent of Catholic priests in Australia had been accused of sexually abusing children between 1950 and 2010.

Source New York Times