From the Editor’s Desk (Wednesday, August 16, 2017, Gaudium Press) Since Hungary became free of communism in 1989, Budapest has emerged as a major European tourist destination. Attracted to the city’s charm, beauty and dramatic history, millions of visitors from around the world have fallen in love with the Hungarian capital.

Travelers to Budapest should not forget to pay visits to St. Stephen’s Basilica, the Hungarian Parliament building, and nearby Esztergom, where important relics related to St. Stephen, to whom the Hungarian people have been steadfastly devoted throughout their history, are housed.

St. Stephen I (975-1038) was the first king of Hungary. His father, the Grand Prince Géza, had converted to Christianity for practical political reasons so that Hungary could become firmly allied with Western Europe. By contrast, Stephen was genuinely devout, although we do not know exactly when he was baptized. As king, Stephen centralized the Hungarian state and fought against pagan influences, thus cementing his nation’s Christian status. He was probably crowned on either Dec. 25, 1000 or Jan. 1, 1001, and it was traditionally said that he received his crown from Pope Sylvester II.

Pope Sylvester’s blessing solidified formerly pagan Hungary’s integral place in Christian Europe. Meanwhile, Stephen decreed that the Church in Hungary would be free of state meddling and answer only to Rome. During his rule, he invited Christian missionaries from elsewhere in Europe to help root out paganism. He was canonized in 1083.

The Hungarians are a proud people with a 1,000-year culture, yet they have often been invaded and oppressed by foreign powers throughout their history, including: the Ottoman Turks, some of the Habsburg Emperors, Tsarist Russia, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. During desperate times, the Hungarians have often clung to their traditions. Paramount among them is devotion to St. Stephen, symbolic of Hungary’s Christian identity. The 2011 Hungarian Constitution begins with the words: “God bless the Hungarians.”

Throughout the centuries, the Hungarian people have cherished St. Stephen’s right hand (called the Holy Dexter) – lopped off by pagan rebels in 1061 and since 1862 stored in a beautiful neo-Gothic silver and glass reliquary – as an important relic. For decades, Hungary’s atheistic communist rulers fought against their people’s devotion to their first king, whose feast day the general Roman calendar celebrates Aug. 16.

However, since Hungary fully regained its independence, a Mass is held at St. Stephen’s Basilica in Budapest each year Aug. 20, the day of the translation of his relics. Thousands of Hungarians flock to their capital and take part in the Mass and a procession of the relic.

Visitors to Budapest can see the most cherished of all Hungarian relics. It is located in a glass case in a chapel to the left of the main altar in the basilica, a masterpiece of Neoclassical art with a Greek cross-shaped floor plan, two towers, and an elevated dome that dominates the Budapest skyline.

Another relic related to St. Stephen that is dear to many Hungarians that the visitor to Budapest can see is the “Holy Crown of Hungary,” or the “Crown of St. Stephen,” which was said to have been given to the first Hungarian king by Pope Sylvester II. Starting in the 12th century, Hungarian kings were crowned with this relic, as were Habsburg emperors, who from 1526 until 1918 also received the title of “King of Hungary.” (Editor’s note: The U.S. had possession after WWII and returned it supposedly to the Hungarian people, not the government, in 1978 after receiving many pledges of its safety.)

Since 2000, the Holy Crown has been located in the neo-Gothic Hungarian Parliament building, widely considered to be one of the world’s most beautiful legislatures. The gold and silver crown is adorned by a characteristically slanted cross, which was probably knocked crooked in the 17th century. Visitors can see the crown during tours of the parliament that take place regularly; however, photography is prohibited

St. Stephen’s coronation took place in Esztergom, which served as the first capital of Hungary, from 1000 until 1256. The town is about an hour-and-a-half by bus from Budapest and is definitely worth seeing. (Also, the Anonim restaurant across the street from the basilica serves the best goulash I have ever eaten.) While Esztergom was once the capital of a major medieval European state, today it is a small town. It is home to the Cathedral and Primatial Basilica of the Blessed Virgin Mary Assumed Into Heaven and St. Adalbert.

One should not be turned off by the long-winded name, as the Esztergom basilica, the largest church in Hungary, is a beautiful 19th-century Neoclassical building perched on a rock and offering amazing glimpses of the Danube River. (The most impressive view is from the basilica’s dome.) The basilica features the dome, two towers and an entrance supported by eight massive pillars.

The high altarpiece inside the basilica is a massive 44-foot-tall neo-Renaissance painting of the Assumption by Michelangelo Grigoletti based on a work by Titian. Other altars are devoted to St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr (not to be confused with Hungary’s first king); Hungarian saints, including St. Elizabeth; and St. Adalbert, the bishop of Prague who taught St. Stephen of Hungary about the faith. The Esztergom basilica’s massive organs were played in 1856, during its consecration; the great Hungarian Romantic composer Franz Liszt composed and conducted his Esztergom Mass for the occasion. It is also worth paying a visit to the cathedral treasury, which contains an impressive collection of medieval religious art (reliquaries, monstrances, chalices, etc.), including the “Coronation Oath Cross” on which Hungary’s kings took their oath during their coronation.

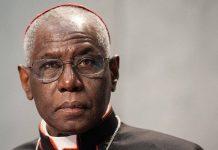

Esztergom is the traditional seat of the Hungarian primates and archbishops of Esztergom-Budapest, who are buried in the basilica’s crypt, built in the “Old Egypt” style. Undoubtedly, the most famous of them was Cardinal József Mindszenty (1892-1975), known for his courageous defense of human rights under communism. Cardinal Mindszenty was imprisoned and underwent brutal tortures, yet he refused to give in to his oppressors. Since the 1990s, his cause for sainthood has been underway. Cardinal Mindzsenty’s tomb features rosaries, flowers and ribbons, with national flags brought by pilgrims from around the world.

Despite being brutally dominated by their neighbors many times throughout their history, the Hungarian people survived because they tenaciously cultivated their culture, which is so firmly rooted in their Christian heritage. A visit to Budapest and Esztergom reveals this inspiring legacy that the Hungarians fought to preserve during many centuries of oppression.

Source National Catholic Register/Filip Mazurczak