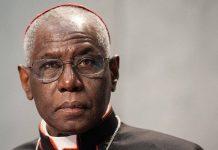

Who was this figure who, though discreet, was able to become – still as a cardinal – “one of the two or three most powerful men in the Catholic Church”? Above all, what was the mission granted to this Wise Man, to whom our Lord entrusted his flock?

Newsroom (31/12/2022 10:30 AM, Gaudium Press) On Wednesday 28th, after the Vatican made its first official statement on the declining health of Benedict XVI, the world turned its attention to the Pope Emeritus.

After a long period of gradually losing his health, Benedict XVI’s life was gradually fading out until the moment when, silent and deprived of that keen, penetrating, lucid look, he was called by God on the last day of the year 2022.

At the age of 95, his eyes were closed to this world.

Who was Benedict XVI?

Now, who was Benedict XVI? How to describe this Pope who shone with unusual intelligence and fine theological sense, to the point of being called the “Mozart of theology”, a “modern day Thomas Aquinas”? Who was this figure who, though discreet, was able to profoundly influence the Second Vatican Council and later the Roman Curia and even John Paul II himself, of whom he was a personal friend, to the point of becoming – even as a cardinal – “one of the two or three most powerful men in the Catholic Church”? Above all, what was the mission granted to this Wise Man, to whom our Lord entrusted his flock?

It is extremely difficult to summarize, in the short space of one article, the life of this singular personage who witnessed some of the greatest upheavals and transformations that humanity and Catholicism have ever gone through.

Perhaps, going back almost a hundred years in time, we can find some answers…

Born to point to the true Church

On April 16, 1927, Germany was on the eve of two major events.

The first of these, in the political field, was a catastrophe. While the country was still getting back on its feet after the First World War, Adolf Hitler and his party were on the rise, and were about to plunge the German nation into one of the darkest nights of its history.

The other event is religious: on the 16th, the entire Church was celebrating Holy Saturday – the eve of Resurrection Sunday – when Christ conquered sin and death. And in this atmosphere, the simple town of Marktl, in Bavaria, saw the birth of a baby boy in poor health, who will be baptized with the name Joseph Ratzinger.

For the moment, none of those present could even imagine how symbolic the coincidence of the dates was. That same child, born in a world shrouded in darkness – Joseph came to light at 4:15 in the morning – was itself called to be, for all humanity, the Precone, the announcement of a Resurrection.

Ratzinger himself commented on this “coincidence” – one might say, almost prophetic – of his birth:

“It gives me great joy to have been born on this very day, the eve of Glory Sunday, just as Easter is beginning, even though it has not begun at all. In addition, it seems to me that it has a very deep meaning, because it symbolizes what in reality is my own story, my current situation: to be at the gates of glory, without yet having entered it.”

But what is this “Resurrection” of which Benedict XVI was called to be the forerunner? We know that the Church does not die, according to the promise made by Jesus Christ himself, even if it seems to succumb, as in certain moments of the life of this Pontiff… However, as long as there is someone to uphold the Faith, good customs and true doctrine, the immortality of the Church will be guaranteed.

Now, the Pope’s mission is precisely this: to guide the flock of Christ; to define, to clarify and to show the faithful what the true Religion is, especially in a world where it seems to have deserted.

It is then that the “Resurrection” takes place, not because the Church was dead in itself, but because, in the eyes of men, it seemed to have died.

Perhaps in 1997 – the date Ratzinger uttered the words quoted above – much of this was already clear to him. When we analyze his life, we realize that the whole of it was leading up to and preparing him for the fulfillment of this mission.

We will only understand Benedict XVI in all his breadth if we analyze him in this light.

A Wise Man: Joseph Ratzinger and the Second Vatican Council

After a simple childhood and a youth disrupted by the Second World War, Ratzinger was finally ordained a priest.

Already in early adulthood, his brilliant intelligence gave him prominence in the academic world. He was pursuing a career as a university professor when another event crossed his life – and this one would also mark it forever: in 1962, Pope John XXIII initiated the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council.

Ratzinger made his debut as the personal theologian to Cardinal Frings of Cologne, and was preparing his pronouncements, many of which carried enormous weight in the conciliar sessions.

The young priest was indeed exhilarated!

It must be said that at the beginning his influence was still relatively small, but this situation did not last long. Some events would change it.

On June 3, 1963, the reigning Pope John XXIII died, and Cardinal Montini ascended to the Papal Solium, under the name of Paul VI. Paraphrasing the words of Pablo Sarto, we can say that, if the late Roncalli was the initiator of the Council, Montini was – before and after his election as Pope – its great “architect”.

With the ascension of the new pontiff, Ratzinger was appointed one of the Council’s experts and, as such, began to attend all the conciliar sessions.

In addition, he became one of the members of the European Alliance, a group formed by several Council Fathers – led in large part by Germans – whose opinions were decisive for the course of Vatican II. During this period, our theologian worked side by side with renowned figures, in particular, Karl Rahner.

If there is one word that sums up Ratzinger’s role in the Council, it is unity. He always defended a position favorable to ecumenism, seeking a convergence of non-Catholic Christians to the unity of the Church – a unity that, for him, is dynamic, never monolithic.

To this end, he sought to avoid certain kinds of definitions that could hurt Protestants in some way, such as Marian devotion, for example.

Dizia ele: “When I was still a young theologian, before the Council sessions (and also during them), as happened and happens today with many others, I harbored certain reservations about old formulas, like for example that famous ‘De Maria nunquam satis’, ‘about Mary one will never say enough’. It seemed to me to be quite exaggerated. Moreover: “Personally, I was at first very determined by the severe Christocentrism of the liturgical movement, which the dialogue with my Protestant friends intensified even more.

Another fact that denoted much of this mentality was the criticism made by Cardinal Frings – whose schemes, we have already said, were coined by Ratzinger – of the methods used by the Holy Office. This Congregation, in other times known as the Holy Inquisition, was headed by Cardinal Ottaviani. Frings’ harsh pronouncement was received with a round of applause by the other participants, and with tears for the offended cardinal… but the latter were not able to stop the proposed reforms.

Finally, to sum up, we would say that Joseph Ratzinger was “the youngest of the wide range of theologians who marked Vatican II, and he is certainly one of the greatest for his spiritual and theological capacity”.

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

After the Council, the expert returned to Germany to teach. But the professor soon disappeared, to give way to that of pastor: Ratzinger was consecrated Archbishop of Munich on May 28, 1977, and a month later named Cardinal by Pope Paul VI.

However, in February 1982, the life of the future Pope suffered again a drastic change in its course: the river of events took him back to Rome, and this time for good…

That month he arrived in the Eternal City, no longer as theologian, nor as Archbishop, but as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (coincidentally, the same one that had been attacked by Frings during the Council)

Armed with his grand piano and his rich library, he settled into an apartment overlooking St. Peter’s Square, opposite his office. This will be the cause of the consecrated image of the Cardinal Prefect, with beret and suitcase, crossing every day one of the most famous squares in the world.

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith – formerly called the Sacred Congregation of the Universal Inquisition and later the Holy Office – is the first of the Roman Congregations, founded by Paul III in the 16th century.

Its work is intense: it deals not only with doctrinal questions, but also with disciplinary and even matrimonial matters, as well as incidences in the Catholic Church, or the well-known cases of abuse by the clergy, in addition to apparitions and mystical revelations.

Here the future Pontiff’s mission was already beginning to be outlined more clearly, especially in his own eyes. Ratzinger would become the great moderator of the truth, the Pope’s long hand to detect error and correct it while there is still time.

In this regard, let us recall some of the traits of his actions during this period.

Throughout 1988, he held a series of talks with Marcel Lefebvre, one of the most radical bishops of the traditionalist wing and one of the biggest critics of the Council’s reforms, to avoid a new division in the Church. But he was not heard. On June 29, Lefebvre ordained four bishops without permission, consummating the schism.

He also played an important role in confronting Liberation Theology, especially with one of the main leaders of the movement, his former student Leonardo Boff. Ratzinger refuted and condemned many of its errors – especially its desire to transform the Church into a political institution with a Marxist character.

Communism, by the way, was also in the sights of the Grand Inquisitor, who called it “the shame of our time”. Needless to say, such an assertion brought him much criticism, including from Cardinals.

He was also prolific in his writings: of the 27 documents of a disciplinary character issued by the Congregation since the Council, 13 belonged to the Ratzinger era; of the 62 of a doctrinal character, 40; as well as 9 of a sacramental character, 12 from the International Theological Commission and 3 from the Pontifical Biblical Commission.

Report on Faith

One of his works that generated more repercussion in ecclesiastical circles was the “Report on the Faith”, or “Ratzinger Report”, as the North American journalists called it.

During his vacation in the summer of 1985, Joseph Ratzinger took advantage of the relaxed atmosphere of the Brixen seminary to give a long interview to Vittorio Messori. His words, however, were in contrast to his surroundings: Ratzinger “reviewed” the whole situation the Church had been experiencing since the Second Vatican Council, and his assessments were as harsh as they were realistic:

“The results that followed the Council seem cruelly opposed to the expectations of everyone, beginning with Pope John XXIII and then Paul VI. […] The Popes and the Council Fathers hoped for a new Catholic unity, and instead there was a move towards a dissension which – to use Paul VI’s words – seemed to pass from self-criticism to self-demolition. A new enthusiasm was expected, and instead it too often ended in boredom and discouragement. A leap forward was expected, and instead we find ourselves facing a process of progressive decay.”

But Ratzinger also pointed to what he thought was a solution:

“We must remain faithful to the today of the Church; not to yesterday or tomorrow. And that today of the Church are the authentic documents of Vatican II. Without reservations that cut them out, nor arbitrariness that disfigures them.

Here it is already possible to glimpse much of his “hermeneutic of continuity”, by which he defended that the Council needed to be interpreted in harmony with the entire two thousand year legacy of the Church, reflected through the teaching of the Popes. On this, he paraphrased:

“Dogmas,” someone said, “are not walls that prevent us from seeing, but quite the contrary windows open to the infinite.

This three-day long interview gave rise to a book, which was entitled “Report on the Faith”. The work went against the opinions of several influential currents within ecclesiastical circles, which sought a break with the past (as if it were possible to admit that everything that the Holy Spirit had inspired in his Church over two thousand years was something outdated and, therefore, disposable). These supporters of the so-called “progressive wing” launched a campaign of criticism – and even threats – against Ratzinger’s book: “In some places, it was even forbidden to sell it, because heresy of this caliber could not be tolerated.

The discussions reached such a point that, in the same year of publication, a synod was convened to discuss the book.

This intransigent attitude earned him again a great deal of criticism from ecclesiastics, theologians, and even politicians, who judged him too harsh, too inflexible, too undiplomatic, in a word: too German. They even called him Panzerkardinal (in an obvious allusion to his country of origin).

So where was the Ratzinger of conciliation, unity and ecumenism that had marked Vatican II?

There seems to have been something of a change in his ways here. The Cardinal Prefect knew the role of the Truth, and knew that it needed to be told, even though it might often hurt some.

However, it must be said that John Paul II did not share the same views as the panzerkardinal challengers. He needed someone like that. Ratzinger was his right-hand man, he had a private meeting with the Pope every Friday afternoon in order to dispatch about the work of the Congregation.

Thus, the Cardinal Prefect went about his discreet life of work, which – in his view – was already coming to an end. According to him, he no longer had any desire, except to retire one day to dedicate himself to his passion: theology. But God’s plans for him were quite different…

A Wise Man leading the flock of Christ

Benedict XVI: The Cooperator of Truth

When John Paul II died, the 115 cardinal electors gathered in the Sistine Chapel. After the fourth vote, concluding one of the three briefest conclaves in history, white smoke rises to the heavens:

“When Benedict XVI was elected pope, an old and worn-out cliché leapt to the streets: Ratzinger was the Grand Inquisitor, the ‘Panzerkardinal,’ God’s rottweiler or – in the Italian version – the ‘German shepherd’… This image came perhaps from hastiness and from his twenty-three years at the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, formerly called the Holy Office, as a collaborator of Pope John Paul II.”

The one who should be the defender of the truth, pointing it out to the whole world and working for its favor, was ascending to the Papal Palace: Christ handed over his flock to a Wise Man.

He was so aware of this that for his coat of arms he chose the phrase from St. John: Cooperatores Veritatis (3 Jn 1:8) – the same, in fact, that appeared on his episcopal coat of arms.

But this was not the only aspect of his pontificate. That unity, of which he had been the champion at the Council, was also present in some form. One Church! In his first homily as Pope, he declared that this would be his program:

“With full awareness, at the beginning of his ministry in the Church of Rome which Peter watered with his blood, his present successor makes it his priority commitment to work with the utmost commitment to re-establish the full and visible unity of all Christ’s disciples. This is his will and his indispensable duty. He is aware that for this, manifestations of good sentiments are not enough; concrete gestures are necessary that penetrate spirits and shake consciences, impelling each one to interior conversion […].

“Before Him, the supreme judge of every living being, each one must place himself, aware that one day he will have to give Him an account of what he has done or omitted for the great good of the full and visible unity of his disciples […]”.

The words of Benedict XVI were severe. Being pontiff, an omission on his part would have catastrophic consequences for the whole Church, and God would judge him accordingly.

Fatima-Brazil: prophetism and hope!

On the other hand, it is also worth remembering what Benedict XVI’s relationship was with us, as Brazilians.

Latin America was for him the “Continent of Hope”, a world still young, and therefore full of life and promises, something that pointed to the future.

Within this, Brazil – then the most Catholic country on the planet – played a very important role: “A fundamental part of the future of the Catholic Church is decided here in Brazil.”

Thus Ratzinger revealed something of his thoughts about the lands of the Holy Cross: he was foreseeing a prophetic mission for this country! And knowing about prophecies was not something foreign to Benedict XVI: let’s remember that one of his tasks as Inquisitor was to carefully guard and investigate those mystical revelations that have been made throughout history.

What he did not reveal, however, was what this mission would be.

Curiously, he said the same thing about the Fatima message when he visited the Shrine in May 2010, exactly three years after his trip to Brazil: “Those who think that the prophetic mission of Fatima is finished are mistaken”.

On that day, Ratzinger recalled that the centennial of the apparitions was approaching, and he hoped that those seven years of waiting would hasten the triumph of the “Immaculate Heart of Mary for the glory of the Holy Trinity.” However, he thought it best not to manifest how he hoped this triumph would come about…

Moreover, like Latin America, Fatima was, according to him, a message of hope.

Fatima-Brazil: prophetism and hope. Is there a connection?

These are mere speculations that may or may not be real. The future will give us elements to judge them.

What is certain is that Benedict XVI saw something providential for Brazil, to the point that he chose only the Brazilian lands, and not those of another Latin American country, to visit.

A Mystery: The resignation of Benedict XVI

At the age of 86, Benedict XVI declared that his advanced age and declining physical strength would no longer permit him to adequately exercise the Petrine ministry, and announced that for this reason, “well aware of the weight of this act and in full freedom,” he resigned the ministry conferred upon him on April 19, 2005.

The unusual act of resignation caused astonishment, especially because of the fact that Benedict XVI would still be Pope, although emeritus. This circumstance was indeed new: whenever there was a Pope’s resignation, he automatically returned to his former status. With Ratzinger the situation would be different…

The uncertainties and instabilities that were anticipated with Benedict XVI’s decision shook many minds: Who would be the next Pope? What line would he follow?

In addition to these unknowns, a certain – to some extent inexplicable – atmosphere of tragedy began to make itself felt: what would become of the Church from that moment on?

Speculation was beginning to swirl in Rome. The names of the papabili were circulating on the feathers of all the Vaticanists. The assumptions about Benedict’s own future were also making themselves felt. Everyone wanted to be anchored to something that seemed solid: man needs certainty. Where were they at that moment? Who could predict the future?

Some tried to rely on the prophecies of the Saints, but this caused even more insecurity. Many of them seemed to portend difficult times.

Blessed Anna Catharina Emmerick, for example, saw two Churches and two Popes. One of the Churches was huge but full of demons, the other one was small but made up of true believers. All very mysterious.

Another prophecy, made by Our Lady to Mother Mariana de Jesús Torres, spoke of the “error of the Wise Man”, because this man had been entrusted with the Flock of Christ, but he delivered it into the hands of his enemies.

The coincidences were impactful, true, but this could not cause the faithful to despair. Here we return to the theme of the immortality of the Church. Those who don’t have faith in this promise of our Lord will never be able to understand the prophecies correctly, and will end up creating even more confusion in their minds. Unfortunately, at the time of the abdication, this was the case.

However, the indisputable fact is that, whether he was wrong or not, that Wise Man, who until then had been leading the flock of Christ, had resigned, becoming a mystery…

Since then, his function as “COOPERATOR OF THE TRUTH” was exercised in another way. No longer with concrete gestures, but from within silence, recollection, and prayer, and this silence was to be maintained until the end of his days.

Benedict XVI was, without a doubt, one of those great men who marked History. He marked it by everything he did, there is no doubt. But I wouldn’t say only that. Key men, such as the late pontiff, have such a capacity to influence, that they mark History even by what they have failed to do.

So, what was left in the depths of this great man’s heart, in that impenetrable chamber, where only God searches, called the heart? What yearnings did he have, in these last days of his life, for the Church and for the future of the Mystical Spouse of Christ, largely drawn by himself?

The true testament of this eminent life, only the future will seal.

Finally, if Benedict XVI marked History as Pope and wise man, despite his mystery, it is very true that, above all, he was a man whom God loved very much, and that was enough for him!

By Oto Pereira