The day on which the Catholic Church’s “feast of feasts” and “solemnity of solemnities” should be celebrated has caused approximately six centuries of controversy between the faithful of East and West.

Newsroom (05/04/2022 10:30 AM Gaudium Press) In the Old Testament, the Passover feast was celebrated at dusk on the fourteenth day of the first month, the month of Nissan, as God himself had communicated to Moses. (Cf. Lev. 23:5).

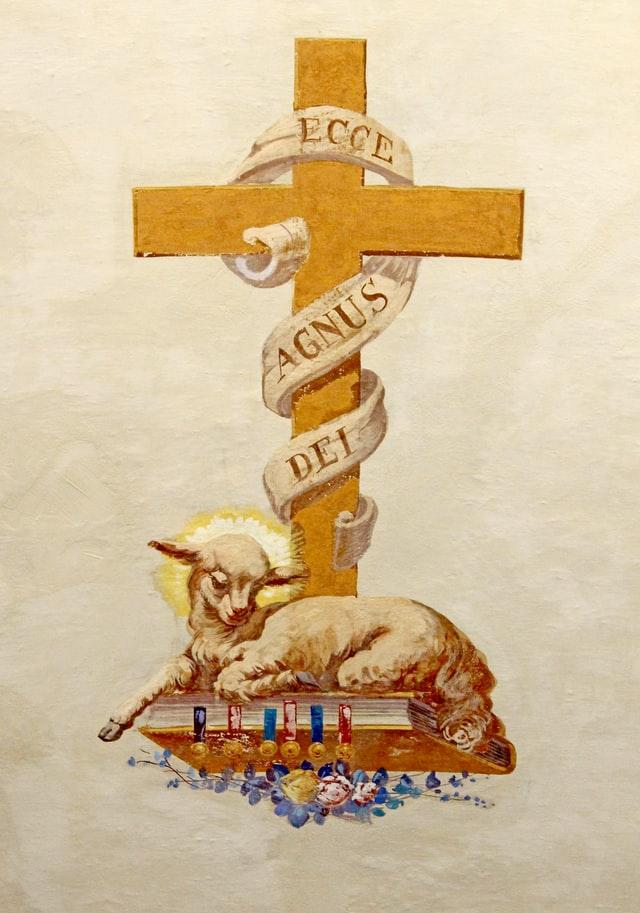

With the supper of the paschal lamb, the Lord had the intention that the people, when celebrating it, would remember their deliverance from the yoke of slavery of Pharaoh, as well as the indulgence he had had with the firstborn of the children of Israel. On the occasion, each head of a family was to sacrifice a lamb and eat it with bitter herbs, in company with all his own.[1]

However, with the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ to earth, the Church, the people of the new law, came to regard Passover as the “feast of feasts” and the “solemnity of solemnities,”[2] for this was the occasion when Christ, our Passover Lamb, was slain to redeem us. Thus, on this great solemnity, the Church celebrates the moment when Christ not only suffered, but, above all, rose again, conquering and destroying the empire of death forever and ever.[3]

This is why, in present times, Easter is celebrated on Sunday, because, according to the Evangelist’s account (Cf. Jn 20:1), that was the day on which the Lord rose from the dead. But it has not always been this way.

Six centuries of controversies

In the early days of the Church, the day on which the “solemnity of solemnities” should be celebrated was the pretext for approximately six centuries of great controversy between the Eastern and Western Churches.[4]

In the second century, in proconsular Asia, the Feast of Passover was celebrated on the same day as the Jews, that is, on the 14th of Nissan, the day of plenilunion. This month in the Hebrew calendar corresponds to the second half of March and the first half of April in the Gregorian calendar. Another part of the Church, however, on the assumption that Our Lord rose on a Sunday, celebrated Easter on this day of the week, probably on the one following the 14th of Nissan.[5]

It is not known for certain whether those who held to the observance of Easter on Sunday celebrated the Savior’s Passion on the Friday preceding such a date. Nevertheless, those who held to Jewish custom probably regarded the 14th of Nissan not only as a memorial of the Resurrection, but also of the Savior’s Passion.[6]

In 314, a first council was convened in Arles in order to establish the exact date on which Easter would be celebrated. It was defined on that occasion that all the Churches had to celebrate the feast on the same day, and that the Pope would send a circular every year to determine the day of the celebration. But still, some persisted in their obstinacy, unwilling to give up the ancient custom of the Hebrew people for the sake of the unity of the Universal Church.[7]

It was only in 325, eleven years later, that the first ecumenical council in the history of the Church was convened, the Council of Nicaea, in order to, above all, combat Arianism. However, since the whole Church was gathered together, it was used to define and settle many things, among them the date for the celebration of Easter in all the Churches of Christendom. Thus, with a view to satisfying both the faithful of Eastern and Western origin, an agreement was reached, which established that Easter would be celebrated on the Sunday following the 14th of Nissan, after the spring equinox.[8]

However, due to different methods used to calculate Nissan 14, the day of the celebration of Easter, even today, does not always coincide in the Western and Eastern Churches.

Thus, even after the definition of Nicea, controversies about the matter persisted, but without any more relevant result that would lead the Holy Father to promulgate another opinion along these lines.

By Guilherme Maia

[1] Cf. SCHUSTER, Ignacio; HOLZMMER, Juan. Historia Bíblica: Antiguo Testamento. Trad. Jorge de Rieu. Litúrgica: Barcelona, 1934, p. 341, n. 326.

[CATECHISM of the Catholic Church. 11. ed. Sao Paulo: Loyola, 2001, 1169.

[3] Idem.

[Cf. VACANT ; MANGENOT; Dictionnaire de Théologie Catholique. Letouzey et Ané: Paris, 1932, V. 11- II, p. 1948.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Idem, p. 1952.

[8] CATECHISM of the Catholic Church. 11. ed. Sao Paulo: Loyola, 2001, 1170; Cf. VACANT ; MANGENOT; Dictionnaire de Théologie Catholique. Letouzey et Ané: Paris, 1932, V. 11- II, p. 1956.