With his music, Mozart was able to convey the luminous response of divine Love, of hope, even when human life is ravaged by suffering and death.

Newsroom (January 6, 2022, 9:10 AM, Gaudium Press) Today we would like to invite the reader to take a stroll through the gardens of history.

Let’s go back two centuries in time and cast our sights on a beautiful city. In its center, St. Stephen’s Cathedral, with its sharp, lacy tower, adorns the panorama; medieval, Renaissance and Baroque buildings blend harmoniously along winding, picturesque streets.

We are speaking of Vienna, capital of Austria, seat of an empire until the end of World War I, the point of union between East and West Europe. Vienna, that the Danube wraps sweetly in its sinuosities along the plain. Vienna, full of life, harmonious and joyful, welcoming and friendly, probably one of the cities that has developed a lifestyle characterized by the douceur de Vivre [1]. Vienna, the capital… of music.

Mozart, the “king of music”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was a Viennese composer who was more capable than any other of expressing the good values of the 18th century in music.

Born on January 27, 1756, his musical talents blossomed very early; in fact, one can say that music was a family affair, already very present in his home: his father, Leopold Mozart, was a great composer and violinist, and played an important role in his son’s musical education. Already at the age of five, Wolfgang composed his first pieces.

When he was six years old, a very unique event occurred. Mozart had the opportunity to present his compositions at the Austrian court. On this occasion, he naively asked the Empress to give his daughter, Marie Antoinette – who would become Queen of France – in marriage.

Those present claimed that he had no title of nobility and therefore could not marry the emperor’s daughter, to which he innocently replied, “But I am the king of music.” Really, he didn’t lie…

The case of Allegri’s “Miserere”

One day in 1770, while he was in the Sistine Chapel attending Holy Week officiated by Pope Clement XIV, he heard Allegri’s famous Miserere performed by the pontifical choir. After the ceremony, he went with the Austrian ambassador to the embassy palace. The young Mozart, who was 14 at the time, hastily retired to his room and began writing in peculiar characters in his notebook.

At dinner, the ambassador commented on the ceremony, lamenting that he could not make Allegri’s Miserere known to the whole world, since the score of the music had never been granted to anyone.

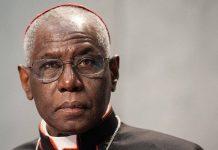

On Good Friday, Mozart was again sitting in the Sistine Chapel listening to the choir singing, but this time looking at the notebook he had hidden inside his hat. A cardinal who was there did not fail to observe him.

In the evening there was a great concert in the Borghese villa, the palace and gardens were lit up, and the melodious sounds of instrumental pieces of music could be heard through the palace windows. At one point, the audience turned to the marble gallery: “It’s him! It’s him! It’s the wonder of our country,” they said of the boy who had just beautifully played some pieces on the harpsichord.

The ambassador approached and, leaning his elbow on the harpsichord, gave him an encouraging look. To everyone’s surprise, the little Mozart began to masterfully interpret the coveted Miserere, to which everyone was surprised: some spoke of a prodigy, others, however, alleged that the score had been stolen. “For it to be so perfect, it must have been written while they were performing it!” some said.

The cardinal, who had watched the boy in the Sistine Chapel during the morning, resolutely claimed that he saw the distinguished interpreter looking at his notebook during the course of the Vatican ceremony. However, the Austrian ambassador, holding the little boy’s hand, replied to the cardinal, “Are you sure of this, Your Eminence?” to which the cardinal replied yes. At that moment, the boy spoke up, saying that while the cardinal was watching him, he was only checking his notes, because he had written everything down from memory from the first time he heard the music.

Another day, the little genius was taken to the Vatican. After passing through a few halls, he was ushered into the papal enclosure. Clement XIV asked him kindly:

– “Is it true, my son, that this sacred music, reserved only for Rome, you have kept it in your memory since the first time you heard it?”

– “It’s true, Holy Father”

– “And how is this possible?”

– “Undoubtedly, by God’s permission,” replied the artist.

– “Yes, God made you a genius,” said the Holy Father, “and you are evidently one of his chosen ones to do such beautiful and wonderful things for the Church.”

His songs didn’t die with him.

Even the last moments of his life were not without the presence of music: while Mozart was composing a requiem mass at someone else’s request, he surrendered his soul to God on March 5, 1791. In fact, this last composition of his would be sung at his death.

His songs, however, were not buried with him. Mozart left us countless compositions that constitute a true cultural treasure. In this regard, Benedict XVI said, “Mozart, in his music […], was able to transpire the luminous response of divine Love, of hope, even when human life is beset by suffering and death.”[2]

By Andrés Sierra and Paulo Rozanski

[1] French expression that literally translates as: “sweetness of living.”

[2] BENEDICT XVI. Discourse at the end of the concert offered to the Holy Father by the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. Castel-Gandolfo, 7 Sept. 2010.

Compiled by Sarah Gangl