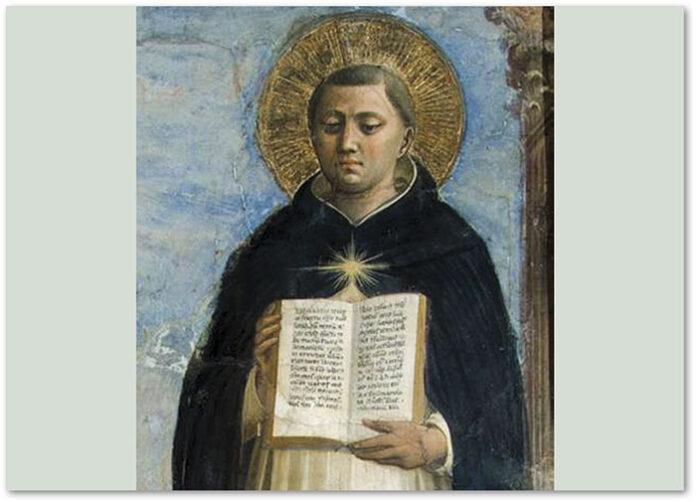

“St. Thomas Aquinas was a great light set by God in the midst of His Church in order to enlighten, comfort and encourage souls throughout the centuries so that they might more gallantly resist the onslaughts of heresy.”

Newsroom (07/10/2024 10:58, Gaudium Press) After St. Thomas had completed his baccalaureate, St. Albert, amazed by the intelligence and, above all, the far-reaching virtues of his young student, took him to the monastery of the Order of Preachers in Cologne, West Germany, where he was ordained a priest in 1248.

Returning to Paris, St. Thomas began teaching at the University, and “drew the attention of students and masters extraordinarily for the novelty of his clear, precise, rigorously logical method, as well as for the calm and serenity of the exposition.” [1] In 1256, he received the title of Doctor together with Saint Bonaventure.

Being a professor at the University of Paris in the thirteenth century was a very high honor. In it there were French, Spanish, Italian, German, English, Dutch, Portuguese, and Greek students. The masters made their expositions in Latin. Such was the importance of this university that “it was the third power of Christendom, next to the Pontificate and the Empire”. [2]

Lauda Sion

In 1259, Pope Urban IV summoned St. Thomas to be his theologian-consultant and to accompany the Papal Court on its travels. He remained in Rome for about ten years attending to the pontiffs, and it was at this time that he began to write the Summa Theologica, his masterpiece.

Wishing to establish an office for the Solemnity of Corpus Christi, instituted a short time before, the Pope asked some of the leading theologians to compose a text and take it to Rome to be presented to him.

When the deadline was over, they met with the Pontiff and St. Thomas was the first chosen to read his writing, entitled Lauda Sion. The praises that the Angelic Doctor, in this song, sang to the Holy Eucharist caused so much wonder in those present that St. Bonaventure tore the parchment on which he had written his text, being imitated by the other theologians.

At the table with St. Louis the King

About 1269, St. Thomas returned to Paris, continued his lectures at the University and wrote treatises for the formation of Catholics, as well as the condemnation of the errors that were then spreading.

At the request of St. Raymond of Peñafort, he wrote the Summa against the Gentiles, in which he demonstrates, by the light of reason, to people who do not have faith the reasons for believing.

The King of France, St. Louis IX, having learned of the holiness and wisdom of the Angelic Doctor, appointed him his advisor.

Once, the saintly monarch invited him to participate in a meal at his table, but St. Thomas respectfully stated that he could not, as he was dictating the Summa Theologica.

The king then went to the Saint’s superior, who ordered him to attend. While the diners talked briskly, Friar Thomas remained silent. Suddenly, he knocked on the table exclaiming in a loud voice: “Modo conclusum est contra hæresim Manichæi! – Thus is the refutation against the heresy of the Manichaeans concluded!“

The superior reprimanded him saying that he was in the presence of the monarch, but the latter ordered his personal secretary to write down the words that the Angelic Doctor would dictate. [3]

On the way to Lyon, attacked by a strange illness

At the insistent request of Charles I of Anjou, brother of St. Louis IX and King of Naples and Sicily, the superior of St. Thomas sent him to Naples to reorganize the teaching of theology at the university. Ecclesiastical authorities begged him to become Archbishop of Naples, but he did not accept and began to teach theology.

In addition to his lectures, he dictated Part III of the Summa Theologica and his commentaries on Aristotle. He frequently celebrated Masses for the faithful, during which he gave magnificent homilies on the Creed, Our Father, the Decalogue and the Hail Mary.

In 1274, Pope Blessed Gregory X summoned St. Thomas to take part in the Fourth Council of Lyon in France. He certainly set off on foot – he rarely travelled on horseback – accompanied by his faithful secretary Friar Reginaldo of Piperno, “but he was attacked by a strange illness”[4].

They took him to Maenza Castle – central Italy – which belonged to his niece, who was a countess. Realizing that his condition was serious, he asked to be taken to the Cistercian Abbey of Fossanova, as he wanted to die in a religious house.

The monks welcomed him with transports of admiration and looked after the saint with care. At their request, St. Thomas began to comment on the Book of Sacred Scripture the Song of Songs.

Simplicity, clarity and supernatural energy

At the point of death, he asked for the Holy Viaticum. When he saw Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament enter his room, despite his extreme weakness, he got up from his bed and prostrated himself before the Blessed Sacrament for a long time, while praying the Confiteor. Then he got down on his knees and prayed this moving prayer:

“Most Sacred Body, price of my soul, viaticum of my pilgrimage!… For Your love, My Jesus, I have studied, preached, taught and lived. My days, my sighs, my labours have all been for You. Everything I’ve written I’ve done with the right intention of pleasing You.

‘However, if there is anything that does not conform to the truth, I submit it to the authority of the Roman Church, in whose bosom and obedience I wish to die.”[5]

As soon as he had received Holy Communion, he went into a deep ecstasy and his soul was taken to Heaven. It was March 7th, 1274. He was only 49 years old.

Full of admiration for the Angelic Doctor, Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira wrote:

“St. Thomas Aquinas was a great light set by God in the midst of His Church in order to enlighten, comfort and encourage souls throughout the centuries so that they might more gallantly resist the onslaughts of heresy.

‘Confronting with his powerful intelligence and his ardent piety all the problems that in his time were open to the investigation of the human mind, he travelled through the most arid, the most obscure and the most treacherous regions of knowledge with a simplicity, a clarity and an energy that were truly supernatural.”[6]

By Paulo Francisco Martos

Noções de História da Igreja

[1] VILLOSLADA, Ricardo Garcia. Historia de la Iglesia Católica – Edad Media.3. ed. Madri: BAC, 1963, v. II, p. 795.

[2] Idem, ibidem. v. II, p. 773.

[3] Cf. GUILHERME DE TOCCO. Ystoria Sancti Thome de Aquino. Toronto: PIMS, 1996, p.174-175.

[4] FABRO, Cornélio. Breve introdução ao tomismo. Brasília: Edições Cristo Rei. 2020, p. 15.

[5] SAINZ, OP, Manuel de M. Vida del angélico maestro Santo Tomás de Aquino, patrono de la juventud estudiosa. Vergara: El Santísimo Rosario, 1903, p.177.

[6] CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. O Legionário, São Paulo. 10-3-1940.

The post St. Thomas of Aquinas: “My days, my sighs, my labours have all been for You” appeared first on Gaudium Press.

Compiled by Roberta MacEwan