The star witness in the Vatican financial trial told judges Wednesday that he was unwittingly encouraged to cooperate with prosecutors by the woman at the centre of the last major Vatican trial.

Newsroom (6/12/2022 7:12 PM, Gaudium Press) — Msgr. Alberto Perlasca, who once led the Secretariat of State’s administrative office, told the court on November 30 that he decided to blow the whistle on his former Vatican department in part because of Francesca Chaouqui, a woman convicted in 2016 of leaking classified Vatican information in the so-called “Vatileaks 2.0” scandal.

In a strange turn of events, Perlasca said he got advice from Chaouqui second-hand through Genoveffa Ciferri, a friend of both Chaouqui and the priest.

The monsignor approached investigators in August 2020 with evidence about corruption in the Vatican’s governing and administrative departments. He told judges on November 30 that his decision came on the recommendation of Ciferri, who claims to have once worked for the Italian intelligence services.

Perlasca, who was for years the chief lieutenant of Cardinal Angelo Becciu at the Secretariat of State, said Friday that his initial 20-page statement to prosecutors, which he presented on August 31, 2020, was drawn up on the advice of Ciferri, who is due to appear in court on Friday.

But it turned out the advice was from Chauoqui, Perlasca said Wednesday.

Perlasca confirmed to the court Wednesday that Ciferri had made suggestions about what material to present to prosecutors and how to draft his statement and said Ciferri had told him she was consulting with a friend of hers to give him advice.

While Perlasca was initially led to believe this was a retired Italian magistrate, Ciferri later told him she had been passing along the recommendations of Chaouqui, convicted in 2016 of Vatican leaking documents.

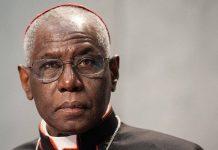

Becciu, on trial for abuse of office and embezzlement, is also facing charges of attempting to influence Perlasca’s testimony.

Last month, an Italian court found the cardinal had abused the legal process by trying to sue Ciferri and Perlasca in the priest’s home region of Como and ordered Becciu to pay nearly 50,000 euros in expenses and damages.

Perlasca’s cooperation was a crucial part of the prosecution’s investigation, which led to charges being brought against ten defendants in July last year and was the subject of months of legal wrangling when the trial opened last year.

The chief prosecutor in the case, Alessandro Diddi, also told the judges on Wednesday that he had received over the weekend a cache of messages between Chaouqui and Ciferri which had led him to open a new investigation. While Diddi did not identify the source of the messages, several people close to the case have said they believe them to have come from Chaouqui herself.

Though Diddi said he did not at present have a specific crime he was looking into, he did not rule out eventually bringing charges against Perlasca.

Vatican prosecutors have faced repeated questions about their decision not to prosecute Perlasca in the sprawling indictment filed in July last year.

Although the former official has cooperated with prosecutors to help them bring charges against his former colleagues, other Vatican senior officials have said Perlasca was a crucial force in blocking audits of the secretariat’s finances and obscuring a range of highly questionable financial deals.

Wednesday marked the third day of evidence from Perlasca to the Vatican court in the past week.

Although he initially claimed his decision to approach prosecutors with a 20-page statement in 2020 was entirely his idea, he then claimed he could not remember who had helped him before acknowledging the involvement of Ciferri and Chaouqui. At several points during his testimony, he was warned about the risk of perjuring himself by the chief judge, Guiseppe Pignatone.

Central to Perlasca’s cooperation with prosecutors, and his appearance before the court this week, have been details of the complicated purchase by the Secretariat of State of a London building in 2018.

The building was acquired from Raffaele Mincione, an investment manager, as part of the secretariat’s decision to withdraw early from a fund set up by Mincione to manage some 200 million euros for the secretariat. The deal was flagged by officials at the IOR, a Vatican bank, and led to the current trial.

The news that Perlasca came forward to cooperate with prosecutors under the advice of Ciferri and Chaouqui adds a new layer of intrigue to the legal process.

The monsignor has provided crucial information to prosecutors about secret transfers of large sums of money ordered by Cardinal Becciu, including to Cecelia Marogna, another self-described intelligence and security expert also facing Vatican charges for embezzlement of half a million euros sent to her by Perlasca on Becciu’s orders.

For his part, Becciu has insisted the money, which Marogna allegedly spent on luxury goods and travel was authorized by Pope Francis personally as part of a plan to ransom a kidnapped nun in 2018.

Last week, the court was told Becciu had his niece secretly record a conversation with Pope Francis about the plan to ransom the nun and the need for the matter to be treated with state secrecy.

On the recording, made just days before Becciu went on trial in Vatican City in July last year, neither Becciu nor Pope Francis mentioned Marogna nor the payments to her.

Also on November 30, the Vatican court heard from Fabio Perugia, a former manager at the Valeur Group. This management company had tried to pitch investment ideas to the Secretariat of State.

Perugia told the court that the Valeur Group had offered to try to help the Vatican unpick the London property deal, which saw the secretariat appoint Gianluigi Torzi, and businessman with multiple links to Mincione, the building’s owner, as its middleman in the process.

Having worked with Torzi in the past, Perugia told the judges the man was “unreliable.”

Torzi is also charged in the current trial, having first been arrested in the Vatican City in June 2020. He is accused of extorting the Holy See for control of the property after he restructured the shares of a Luxembourg holding company he used to convey ownership of the building in the middle of the deal — leaving the Vatican with nominal ownership but himself in total control of the asset.

Perugia also spoke in court about several attempts he made to bid for the secretariat’s business. Still, he said that every proposal he made had been “blocked” by Fabrizio Tirabassi, a former administrator in Perlasca’s team, and Enrico Crasso, a banker-turned-investment manager for the secretariat.

Both Tirabassi and Crasso are defendants in the current trial.

Both men, he said, appeared to steer the secretariat’s business to Crasso’s former bank, Credit Suisse, which, he said, would pay fees to Tirabassi.

Tirabassi had a similar arrangement with another Swiss bank, UBS, which paid him a commission for Vatican business he steered their way, worth millions of euros to the Vatican staffer.

When he worked at Credit Suisse, it was Crasso who, in 2014, introduced the Secretariat of State to Raffaele Mincione, the manager who would end up selling the Vatican the London property.

Crasso left the bank shortly after and founded Sogenel, an investment company through which he managed the Centurion Global Fund, into which the Secretariat of State invested tens of millions of euros, including money from Peter’s Pence, the annual worldwide collection to support the ministry of the pope.

The fund famously invested in several Hollywood films, including Rocketman, the Elton John biopic. Previous reporting has established that all the fund’s investments were held through a small Swiss bank in Lugano, Banca Zarattini. In 2018, U.S. prosecutors named that bank in indictments during a $1 billion money laundering case related to the Venezuelan national oil company PDVSA and Nicholas Maduro. Funds held at the bank were identified for seizure in the case.

In December 2019, Pope Francis ordered the fund liquidated after media reports on its investments.

In addition to charges of fraud, embezzlement, money laundering, extortion, and other crimes related to his work with the Secretariat of State, Crasso is also accused of duping the Vatican into a 7 million euro investment, supposedly to buy a bond issued to raise money to finance the construction of a highway in North Carolina.

The highway and the bond never existed, and the money was used to fund an equity stake in three Italian companies. Crasso later told Vatican prosecutors that he had “never heard of North Carolina.”

- Raju Hasmukh with files from The Pillar