Devoted to Our Lady and a lover of poverty, St. Stephen Harding, whom the Church celebrates on 28 March, was a founder of the Cistercian Monastery in France, where as abbot, he received St. Bernard of Clairvaux with his 30 companions. He founded twelve monasteries.

Newsroom (28/03/2025 08:32, Gaudium Press) A rebellious monk became a Saint?! In fact, not just one, but three. These monks led an escape from the monastery, bringing many behind them. Where did they go? To take refuge in a swamp and start all over again… ‘What madness!’ you might think. Yes, dear reader, it is holy madness, for ‘the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men’ (1 Cor 1:25).

A young man in search of an ideal

Born in England of noble blood, Stephen’s education was entrusted to the Benedictine monastery of Sherborne from an early age. It is believed that he never took his religious vows. Having reached a mature age, he decided to leave the cloister to continue his studies. To this end, he went to Scotland and then on to Paris, where, after saturating himself with the profane sciences, he gave himself over to the search for true wisdom.

Desiring a direction for his life, he undertook a pilgrimage to Rome with a companion whose name history has not preserved. Both decided not to talk during the journey, but only to recite the Psalter. After visiting countless churches and praying at the relics of the Apostles, they returned to France, where Providence had something in store for them.

Having heard about the Monastery of Molesmes and the holy life led there, Stephen’s heart immediately turned toward it, resolved to give himself to God. He imagined that his friend would follow him too, but his aspirations were different. Arriving at the monastery, he was warmly welcomed by Abbot Robert and his prior, Alberic, who would become Stephen’s inseparable companions.

Sad situation of the Monastery of Molesmes

Founded by Robert himself, Molesmes had adopted the Benedictine rule, which was characterized above all by praise for God and austerity of life. However, by the time Stephen entered the monastery, a certain decadence had already begun… Little by little, the ambition for possessions grew and the love of poverty, a legacy from St. Benedict himself, waned, leading the monks to disobey the abbot.

The abbot was strongly opposed to such innovations and, realising that the religious did not wish to live up to the ideal of the foundation, decided to leave. Stephen, who had also noticed the obstinacy of his brothers in habit, suddenly found himself deprived of his spiritual guide and without direction in the very monastery where he had hoped to fulfil his vocation.

Alberic took over as abbot, seconded by Stephen, and both endeavoured to continue the task begun by Robert, but to no avail. They also decided to leave the monastery and live as hermits in a neighbouring region. In the meantime, Pope Urban II asked Robert to return to Molesmes, and the two monks followed him.

The majority of the community, however, did not want to make amends. Together with Alberic, Stephen drew up a list of twenty irregularities in the monastery that represented clear transgressions of the rule of St. Benedict, such as dispensations from manual labour, continuous visits from nobles, comforts and luxuries incompatible with the state they had voluntarily embraced. All this meant that they lived more like feudal lords than religious. With such a list in hand, Robert tried to correct the monks, but they remained recalcitrant.

Cîteaux, the origin of a feud

With no remedy other than a retreat, those ‘three rebellious monks’ – as the famous work on their feud by Fr. Mary Raymond Flanagan, OCSO, immortalized them – went to the Bishop of Lyon, accompanied by four other brothers, and asked for permission to found a new monastery whose way of life would return to the primitive integrity and purity of the rule. Having obtained this approval, fourteen more religious joined them and, on 21 March 1098, the expedition set off for Cistercian, a wild and uncultivated land in the middle of an uninhabited Burgundy forest, more like a swamp.

With the permission of the lord of the land, they cut down the trees on the site and with the wood erected the new monastery, dedicated to Our Lady as would henceforth be all the houses founded by the Benedictine reform.

A year passed peacefully under Robert’s direction, but he was not destined to see the full fruits of his endeavours… The monks he had left claimed him back, and the Pope expressed his desire for him to take over the Abbey of Molesmes. Completely submissive, Robert said goodbye to his little son, whom he would never see again. He would die eleven years later, having lived holily under the unfortunately mitigated rule, contrary to his desires, but in accordance with God’s will.

Joy amid the rigour of the rule

Alberic was elected Abbot of Cistercian, and Stephen, Prior. They soon adopted a white or greyish habit, contrasting with the black habit of the Benedictines, perhaps to symbolize purity and joy in the midst of penance.

The life of the monks was not for everyone… They woke up around midnight and never went back to sleep, interspersing the chants of the Office with the manual labour necessary for their sustenance, during which they gave themselves over to meditation. They attended Mass daily and ate only two meals – on fast days, only one – which consisted of rough bread, a few vegetables and a thin drink. The Abbot, for his part, had to eat with a poor person or pilgrim who came to the monastery looking for food.

A Cistercian monk’s day was spent in strict silence, closely united to Our Lady and in complete anonymity. Among other activities, they also copied ancient manuscripts, and St. Stephen himself undertook a revision of the Latin translation of the Bible from Hebrew.

St. Stephen is elected abbot

In 1109, five years after the foundation of Cîteaux, Alberic died and Stephen was unanimously elected as the monastery’s third abbot.

His first act was, on the surface, to cut off all earthly support and protection for the monastery, by forbidding the nobles who attended the Cistercian church during liturgical festivities to do so accompanied by their courts, whose worldliness was in stark contrast to the ideal of austerity in the cloister. However, despite such a drastic measure, he did not lose the favour of those who wished to help him out of true love for God.

After only a year in his new post, hunger made itself felt in the monastery. One day, the provider monk went to St. Stephen to tell him that they had run out of food. Both men went out to beg for food. The first seemed to have succeeded, but what he got came from a priest whom the Abbot knew to be a simoniac, one who partakes in the buying or selling of ecclestiastical privileges… He immediately ordered all the provisions to be returned and to trust in the help of Providence. His righteousness was not long in being rewarded: a few days later, help arrived at the monastery gates, without the origin of the favour being known.

On another occasion, he sent two monks to the village of Vézelay to buy three cartloads of food, clothes and other provisions, with only three denarii that he had found in the monastery… Trusting in Stephen’s order, they set off. On the way, they heard about a dying man who wanted to help the poor, to make up for his faults and rest in peace. He ordered them to buy everything they needed, and they returned to Cistercian with three wagons overflowing with supplies, each pulled by three horses. From that act of supreme abandonment and trust in Providence onwards, the almsgiving of generous souls never ceased.

An even tougher trial

However, material hardship was not the worst of the trials the Cistercians endured. Since its foundation, only one novice had knocked on the doors of the monastery wishing to join. And as the years went by, it was not uncommon for the bells to ring, interrupting the chanting of the Office, for the monks to rush to the bedsides of dying brothers: ‘The crosses and tombs silently multiplied […] in the cemetery, but no novice arrived to fill the empty stalls of the deceased.’

Stephen feared for the continuity of the fledgling institution and, as he watched one more die, he asked him to come back after his death to tell him if the monastery was pleasing to God and what the lack of vocations was due to. The monk promised and gave his soul to God.

A few days later, Stephen was in the countryside when the recently deceased monk suddenly came to him. He revealed that he had been saved thanks to the state of life he had embraced under the direction of the holy Abbot, and that his work was pleasing to God. As for the lack of monks, he assured him that this sorrow would soon turn to joy. The influx of vocations would be such that the religious would be forced to exclaim with Isaiah: ‘This place is too tight for me, give me room to dwell’ (49:20)

Still submissive to his Abbot on earth, the monk – already a partaker of eternal bliss – asked him for his blessing, claiming he could not leave without permission. Stephen gave his blessing and he disappeared. Fifteen years of apparent sterility were about to come to an end.

A new blossoming

The year 1113 opened and one April day, the doorkeeper monk ran panting to St. Stephen to tell him something unheard of: thirty-one knights were asking to be admitted to the monastery! Bernard of Fontaine – the future Saint of Clairvaux and glory of the Cistercian Order, whose works would be even greater than those of its founders (cf. Jn 14:12) – was indeed there, accompanied by thirty relatives and friends whom he had brought with him to embrace holiness.

The promise was beginning to be fulfilled: ‘Not a week went by without a knight coming to beg Stephen to consecrate him to Christ’.

In a short period of two years, four new monasteries were founded: La Ferté, Pontigny, Morimond and Clairvaux; the so-called Cistercian affiliations, from which the Order would flourish. Twelve monks were sent to each community, the number representing the Apostolic College. Who would be the abbot of the most recent foundation? To everyone’s surprise, Stephen chose Bernard, only twenty-five years old and just out of the novitiate, but who would soon become a beacon for the whole of Christendom.

In 1118 there was a total of nine Cistercian abbeys, and by the end of St. Stephen’s life, ninety houses of the Order had been founded, including one in England, our Saint’s native country, as well as countless women’s convents. But how could unity of ideals and objectives be guaranteed between all of them, despite the distance?

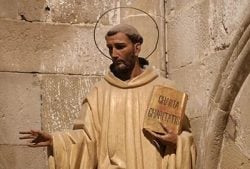

St. Stephen determined that every year the abbots would meet to discuss the affairs of their respective monasteries, in order to maintain the cohesion of the nascent Order; in addition, they should visit the mother abbey, Cistercian, every year, and each abbot of the first four houses – the ‘elder daughters’ – should visit those born from it, thus creating an interconnection between all of them as members of a single body. In 1119, Stephen also drew up the Charta Charitatis – a compilation of statutes and rules that all abbeys had to follow, based on the law of charity – which was approved by Pope Calixtus II in December of the same year.

Stephen’s death and the fruits of the Cistercian Order

Stephen, officially considered the founder of the Cistercians, had lived in the seclusion and solitude of Cistercian since he arrived there, leaving only five times for important matters concerning the Order.

At the end of his life, he was blind and decided to elect a successor. A monk by the name of Guy was chosen, who enjoyed a good reputation, but this was no more than a façade. While the monks were obeying him, Stephen saw an evil spirit enter the newly elected abbot, but he could say nothing. All he could do was pray…

After less than a month, Guy’s unworthiness became clear to everyone and he was removed from office. When another chapter met, they elected Raynard, one of St. Bernard’s first companions and a friend of St. Stephen’s since then. The Order was in good hands.

On his deathbed, when they assured him that he could go to Heaven in peace, the holy Abbot replied in all humility that he was going to God fearful of not having done any good on earth, hoping to have profited from the grace that Providence had placed in him. And so he gave up his soul on 28 March 1134.

Soon, Cistercian abbots would be elected bishops of the regions where they were located and summoned to take part in Church Councils; they would even influence the military Order of the Knights Templar, whose rule was written by St. Bernard, and that of Calatrava, founded by a ‘white monk’, as they used to be called. From a single monastery built in a marsh in France, the great Cistercian Order spread throughout the world, reaching its peak with seven hundred and thirty male and female monasteries. From it would emerge centuries later the Trapa, which would adopt an even more rigorous lifestyle.

Countless saints, mystics and doctors make up the glory of Cîteaux today, such as St. Bernard, the singer of Our Lady, and his brothers; St. Lutgard, St. Gertrude and St. Maud, confidants of the Sacred Heart of Jesus; St. Elred of Rielvaux and St. William of Saint-Thierry, spiritual authors; among many other blessed people.

Like a small spark capable of setting fire to an entire forest, St. Stephen Harding acted on Christendom without leaving Cistercian. Perhaps he himself is not as well known as the countless fruits that came from his fidelity.

Text taken, with minor adaptations, from the magazine Heralds of the Gospel no. 279, March 2025. By Sr Adriana María Sánchez García.

Compiled by Sandra Chisholm