Throughout His public life, Our Lord faced great battles and struggles against the errors of His time, in order to be an example for all the centuries. Today, what is the attitude of a Catholic facing the errors of our time: condescension or intolerance?

Newsroom (20/10/2021 8:45 PM, Gaudium Press) – Often, when we are faced with a decisive situation, we are confronted with thoughts such as: “judge well”, “analyze adequately”, or “be prudent”.

However, what is prudence?

It can be understood as a quality acquired through careful and excellent reasoning, especially in decisive circumstances, when one is able to distinguish which consequences are favorable or not to the subject. As a result, the arguments are sensible, the words are correct, and even the smallest gestures are regulated with due caution, avoiding possible misunderstandings, disagreements, and confusions that may turn out to be unfavorable.

However, it would seem that this applies more properly to certain facts in which error is clearly or veiledly presented, or in those cases in which ideologies deviate from the truth are shown. At such moments, according to a one-sided conception, “prudence” always seems to advise against attacking or denouncing the faults and deficiencies of others. In fact, to throw oneself into difficulties or to be overly demanding are not the attitudes of a prudent man; when there would be no need to expose oneself with harsh and severe words, generating disharmony, opting for the path of dialogue. After all, everything gets on track with soft and affable words…

Is this really its authentic meaning?

St. Thomas Aquinas, based on Aristotle, defines prudence as “the right reason for acting,[1] for what ought to be done.”[2] He explains that it is a virtue that enables man to reason about the good and useful means for achieving a certain good end. [3] According to the Aquinasian expounds, any failure that there is with regard to the attainment of this end will be sovereignly contrary to prudence; for since the end is, in every order of things, the most important thing, so is the failure with regard to the end terrible.[4]

However, relativism more than ever reigns supreme in our age. For the establishment of a supposed “world peace”, the means to achieve this order, this consensus and understanding among all men, is thought to oblige to allow and to yield in most cases to certain errors and faults, and, so to speak, to “condescend to evil” for the sake of this longed-for “peace”.

Is this the path that the Catholic should embrace?

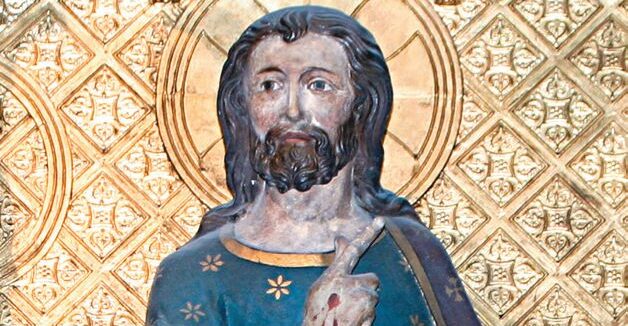

Jesus’ Radicality

The long days of Our Lord’s public life are recorded in the Holy Gospels. There are several situations in which the Divine Master was faced with intricate circumstances, as for example, on the occasion when the tax collectors asked Him for the temple tax. Jesus ordered St. Peter to throw the hook into the sea and collect the coin that would be in the mouth of the first fish found, in order to pay the tax of the two, for as He said: “It is not fitting to scandalize these people” (Mt. 17:24-27). However, his prudence was not only manifested in his divine cunning, but also in his radicalness.

This radicalism, expressed in the alliance between prudence, fortitude, and justice, in no way allowed Jesus to condescend to the wicked but denoted a complete intransigence and belligerence against the vices and iniquities of his time.

We see in Jesus’ teachings a radical intolerance against sin: “If your hand causes you to fall, cut it off; it is better for you to enter life crippled than to have two hands and go into the unquenchable fire of hell” (Mk 9:43). In the episode of the expulsion of the peddlers from the temple, Jesus weaves a whip, overturns the tables of the money-changers, expels them all from the premises, and utters the strict words: “Take it away and do not make my Father’s house a house of merchandise” (Jn 2:13). We also see the Pharisees and Sadducees being constantly rebuked by Jesus, who calls them “an adulterous and perverse race” (Mt 16:4), “hypocrites” because they honored Him only with their lips (cf. Mt 15:7), “whitewashed sepulchers” (Mt 23:27), “serpents and a brood of vipers”: “how will you escape the punishment of hell? (Mt 23:33). The incessant “woes,” a symbol of divine curse, are uttered against them throughout St. Matthew’s chapter 23: “Woe to you teachers of the law and hypocritical Pharisees, you cleanse your cup and plate on the outside, but inside you are full of theft and intemperance” (Mt 23:25- 28). “Truly, I say to you, they have already received their reward” (Mt 6:16).

In short, countless are the passages that describe Our Lord’s radicalness and intolerance toward sin and the wicked.

I did not come to bring peace…

However, in many environments, wouldn’t this radicalism sound imprudent? Would it not be more appropriate to take more benevolent, conciliatory and less forceful attitudes than these?

Here are Jesus’ words: “Do you think that I have come to bring peace on earth? I have not come to bring peace, but division” (Luke 12:51). “Division,” why?

Because “everyone who proclaims the love of God will begin by dividing and breaking up.”[5] The virtue of justice demands of prudence that what belongs to Him be given to God, that is, that the truth not be half-told, but proclaimed. And fortitude calls on prudence that sin and error be denounced without fear or trepidation, for “the reign of God in Jesus, manifested by the casting out of demons and the struggle against their fierce enemies, no longer allows for neutrality. It is necessary to choose.”[6]

Therefore, the Catholic should not be afraid to follow in the footsteps of his Shepherd, for with His coming to earth, “radicalism has come to encompass the whole of Christian existence.”[7]

By Guilherme Motta

[1] Recta ratio agibilium.

[2] TOMÁS DE AQUINO. Commentary on the Nicomachaean Ethics of Aristotle liv. VI, lec. IV, 852, Navarra: EUNSA, 2010, p. 372.

[3] Cf. S. Th. II-II, q. 47, a. 4. In: Ibid. Summa Theologica. Sao Paulo: Loyola Editions, 2005, v. 5, p. 591-592.

[4] Cf. S. Th. II-II, q. 47, a. 1. In: Ibid., p. 587.

[5] MATURA, Tadeo. El radicalismo evangélico. Retorno a las fuentes de vida cristiana. Madrid: Claretian Publications, 1980, p. 190.

[6] Ibid., p. 187

[7] Ibid., p. 18.

Compiled by Camille Mittermeier