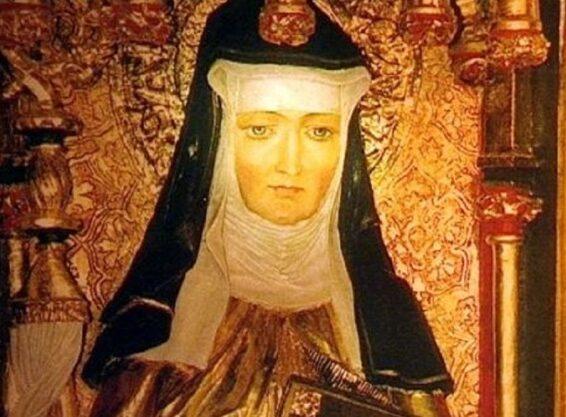

September 17, the Church also remembers the memory of St. Hildegarde of Bingen, a 12th-century Benedictine mystic and nun, called to a special union with the Creator and to the mission of pointing the way for humanity.

Newsroom (17/09/2021 10:33, Gaudium Press) – On a pleasant summer’s day in 1098, the tenth child of Hildebert and Matilda of Bermersheim was born in the castle of Böckekheim on the Rhine. She was a lovely baby girl, baptized with the name Hildegarde. Despite her frail health, she showed – from the very first years of her life – an acute intelligence and religious inclination.

Providence wanted to attract this angelic child to Himself very early, and she was already favored with celestial lights and revelations at the age of three. Thinking that everyone received the same kind of favors, she enthusiastically commented on the beauty of what she saw, causing amazement and wonder in those who heard her.

A Predestined Girl

One day, walking with her servant around the castle, she exclaimed radiantly, “Look at that little calf, how beautiful it is! All white, with spots only on his head and legs. Ah! There’s one on his back, too!”

The maid, looking around and seeing nothing, asked her where the calf was. Not understanding how she could not see the little animal, the girl pointed to a large cow and said incisively, “It’s over there! It’s over there!”

Perplexed, the woman thought she was hearing yet another childish fantasy, and jokingly told Hildegarda’s mother what had happened. However, some time later a calf was born and no one laughed any more: it had exactly the aspect predicted by the little girl!

In the Silence of the Cloister a Great Future Germinates

Since Hildegarde showed clear signs of a contemplative vocation, and the noble countess Jutta of Spanheim had at that time abandoned her worldly glories and riches to become a Benedictine nun, Hildegarde’s parents did not hesitate to entrust their daughter’s education to the zeal of this virtuous woman.

Thus, at the age of eight, she entered the hermitage of Disibodemberg, where she “grew in grace and holiness” after the example of the Child God.

The silence of the cloister, the wise guidance she was given, her participation in the liturgy, and the charism of St. Benedict molded her soul according to the purest monastic ideal: to reflect in every aspect of her life the divine perfections of Jesus Christ.

There was, however, one factor that united her especially to God: the supernatural communications of which she was the object. Beginning with visions in early childhood and continuing throughout her life, they gave her a profound insight into the workings of good and evil, grace and sin, the fulfillment of the will of God to which man is called, and the ease with which he can despise God’s plan.

This wealth of understanding was given to her in order to fulfill her mission to the great of the world, to the poor of the people, and to posterity throughout the centuries.

In fact, St. Hildegarde’s teachings are as relevant today as they were when she lived more than 800 years ago.

A Wonderful Understanding of the Universe

In the thirty years that Jutta led the monastery, Hildegarda made great progress on the spiritual path. When the abbess died, the community found in her disciple the ideal successor.

Much to her regret, facing inner admonitions that dictated humility, Saint Hildegarde bent before the yoke of obedience and began to guide those chosen souls. She carried out this task with such perfection that she had to found two new monasteries – Rupertsberg in 1148 and Eibingen in 1165 – to accommodate the many vocations that came to her.

It was during the fifth year of her time as abbess when the divine voice that accompanied her gave her an express order: “Manifest the wonders you learn. Write and speak!”

Thus originated St. Hildegarde’s main written work, “Liber Scivias,” which received no less than the praise of St. Bernard of Clairvaux and the approval of Pope Eugenius III. Both recognized in her words and her life the authenticity of the revelations.

But, after all, What is the Content of her Teachings?

In a language free of any literary pretension, and full of the color typical of her time, St. Hildegarde speaks about the relationship between God and man, about reation and the Last Judgment, and insists on the role of the Church in the history of salvation.

Her filial heart overflows with exaltations to the Holy Trinity, does not exclude vigorous denunciations of the moral errors of mankind, and speaks of the importance of the sacraments in the sanctification of souls.

For her, the created universe is an admirable mirror of the spiritual and divine realities: “God, who made all things by an act of his will and created them to make his name known and honored, is not content to show through the world only what is visible and temporal, but manifests in it those realities that are invisible and eternal. This is what has been revealed to me.”

A soul full of Divine Knowledge

However, if St. Hildegarde managed to surprise scholars throughout the ages, it was mainly for her bold medicinal claims.

She demonstrated a comprehensive penetration into the relationship between man and the world, its spiritual and physical constitution, and the beneficial properties of living things. She authored the only two medical works composed in the West during the 12th century that we know of.

She states that nervous and spiritual imbalances are inevitably reflected in bodily health, giving rise to the metabolism problems that lead to depression.

At no time does St. Hildegarde fail to consider the mutual influence that body and soul exert on each other. In her opinion, religious life must seek a wise balance between the two factors.

She also defends the thesis that health is essentially maintained by a healthy diet, and she dwells on explaining with richness and depth the characteristics of hundreds of medicinal and nutritious plants. Not even stones escape his analysis, being seen as excellent channeling elements for human energy.

And if this vast knowledge was not enough, Saint Hildegarde was also a remarkable musician.

Gifted with rare acuity, a beautiful voice, and originality, she composed around seventy symphonies according to the styles of her time. Here is what she says about music:

“Let us remember that with sin Adam lost his innocence and, as a consequence, he also lost the voice he once possessed, similar to that of the angels in heaven. Having lost this ability to praise God, the prophets, inspired by the Holy Spirit, invented psalms and canticles to urge men to turn to that sweet memory of praise which Adam enjoyed in Paradise. Musical instruments, too, by the emission of manifold sounds, can instruct men spiritually.”

A woman Preaches in the Cathedrals

At the juncture of the society in which the holy abbess lived, the Church was experiencing dangers that compromised the peace and salvation of souls. The Pope was being persecuted by Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, who, believing himself to possess greater spiritual power than the Successor of Peter, felt he had the right to dethrone him and put in his place whoever favored his ambitious intentions.

The Cathar heresy, which would so deeply mark the epoch, had just erupted, in a delirium of aversion to life and the true God. Finally, a visible relaxation of morals reigned, gradually leading men into the abyss of perdition.

St. Hildegarde did not restrict her action to the monastery; it was necessary to make her prophetic voice resound in the vaults of the churches, to point out with her wisdom the errors of a century deaf to the voice of God; a fervent soul needed to make the doldrums of lukewarmness tremble.

She sets out, in her old age, to preach – something unthinkable – in the great cathedrals filled with clergy, nobility, and people, eager to hear her just admonitions.

Successively, the cathedrals of Mainz, Bamberg, Trier, Cologne, and many others were the stage for his apostolate. The effects were not to be expected: conversions multiplied, and the reputation of the holy abbess as a thaumaturge spread, and her words were followed by miracles.

Besides preaching, she sent many letters to various personalities, always exhorting them to a greater observance of the Gospel.

At the age of 81, without bending before the weight of toils and sufferings, she who never refused help to the children of God delivered her soul amidst the great peace and serenity of her monastery. It was September 17th, 1179.

Text adapted from the magazine Heralds of the Gospel, n. 69, September 2007.

Compiled by Camille Mittermeier