Egypt has many stories to tell us, for from very early on its inhabitants created their own system of registration: hieroglyphics.

Newsroom (06/12/2022 6:44 PM, Gaudium Press) Leaving aside the history of writing in famous Mesopotamia,[1] let’s look at another important ancient civilization: Egypt. How many pages are dedicated today to narrate what happened in this place full of wonders and mysteries! The land of the pharaohs has a lot of history to tell us, and we can have access to it, because from very early on its inhabitants created their own system of registration.

Among the various models of writing that are called pictographic – in which each drawing represents a word or an action in the sentence to be constructed – Egyptian hieroglyphs can be considered the most elaborate.

The history of Egyptian culture dates back to the fourth millennium before Christ, where it was assumed that there were two great kingdoms, one of which was located in the upper course of the Nile and extended to the falls of Assuan, and the other had its central point in the Nile delta. Around 3100 B.C., these two kingdoms were unified by Menes, with whom the first of the great 30 Egyptian dynasties began.

“Altogether, the history of Ancient Egypt is divided into the Old Empire, covering the first ten dynasties, to which belong the great builders of the pyramids of Cheops and Chephren; the Middle Empire, covering from the eleventh to the sixteenth dynasty, lasting until the year 1570 BC; and the New Empire, during which, in an alternation of rise and decline, hard battles for survival ensued. And finally, it ends in the progressive decay of the Egyptian empire, defeated and occupied first by the Ethiopians, then by the Assyrians and, in the sixth century, by the Persians; finally, in 332 BC, by Alexander the Great.”[2]

The “sacred notches”

The oldest form of Egyptian writing appeared at the beginning of the Ancient Empire. It was named hieroglyph by the Greek Clement of Alexandria, who lived in the 3rd century BC, which literally means “sacred carving” (ιερός = sacred and γλύφω = carving) and is found mainly on monuments carved in stone.

“Hieroglyphs were considered a kind of secret writing and served mainly religious purposes; their knowledge was limited to the priestly caste, who trained their scribes in their own schools.”[3]

As early as 30 B.C., Rome took over Egypt. “At this time, the knowledge of hieroglyphics apparently suffered a setback; because of the advance of the Greeks in those regions, they began to write the Egyptian language with Greek characters. The last known document in hieroglyphic writing dates from 394 AD.”[4]

The Corsican, the linguist and the rebirth of dead writing

Many centuries have passed. In the year 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte decided to strike a blow against the French enemy, England. Since it was impossible to defeat them directly by landing on the English south coast, the Corsican leader decided to attack India, which was at the time a British colony, by landing in Egypt, which would serve as a platform for the French army to quickly land in the Red Sea and cut off the passage to the desired country. This was a real misfortune for Napoleon, as he met Admiral Nelson’s powerful British fleet at Albuquir. But these French ventures, though failed from a military point of view, brought great advances to Philology.

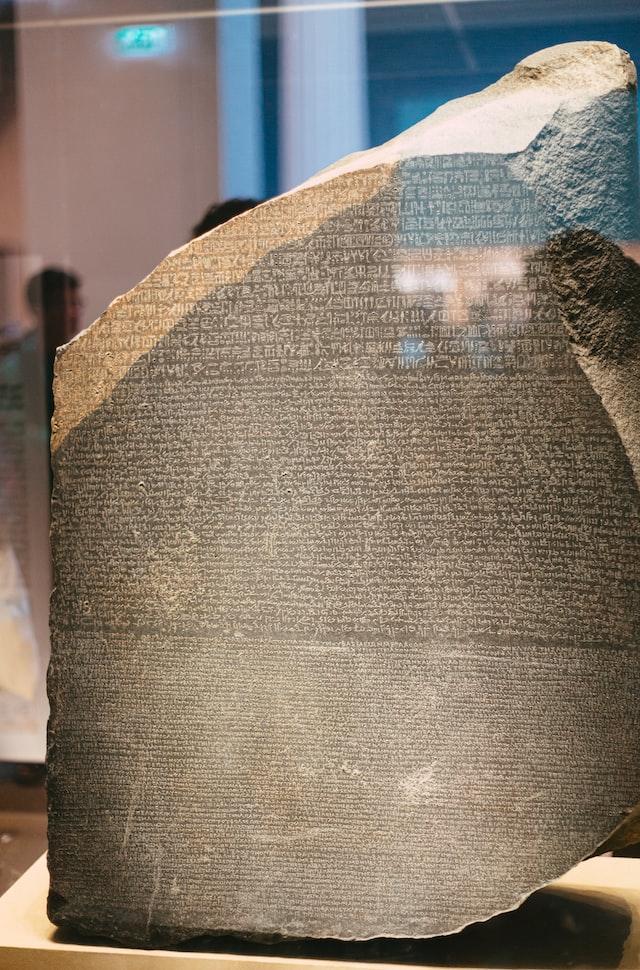

It so happened that Napoleon took many archaeologists with him to Egypt in order to increase knowledge about the enigmatic culture of this country. And between searches and studies, they found in 1799, in the vicinity of the ruins of Raschid, located a short distance from the western part of the Nile Delta, a black basalt monolith measuring 1.14 m high, 70 cm wide and 30 cm thick, now known as the Rosetta Stone.[5] In 1799, they found a black basalt monolith measuring 1.14 m high, 70 cm wide and 30 cm thick, now known as the Rosetta Stone.

“The block bore on the front three inscriptions: above, 14 lines in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, missing the beginnings and ends of the lines; below, 32 lines, partly illegible by the action of time, in so-called demotic writing, known by research from Egyptian papyri (but which could not be read), and below it 54 lines in Greek writing and language, half of them destroyed at the end of the lines.” [6] Because of the “trilingual” style of this monument, the Rosetta Stone was a decisive factor in the knowledge of hieroglyphic writing.

Its discovery was soon publicized among European scholars, and, joining the inscriptions of the monolith, several other documents aided the study of this writing and language. But the delay and the excessive work in deciphering them were elements that caused most professionals to give up… until in 1801, a boy of only eleven years old became aware of the great difficulty in decoding the Egyptian hieroglyphs contained in the Rosetta Stone. His name was Jean-François Champollion.

More than two decades of effort…

Learning of the problem and of the failure of previous philologists, he decided to devote his life to this arduous task. The work required an unusual intellectual effort that, being so difficult, took no less than 21 years to succeed. “In 1824, in his book Précis du Système Hiéroglyphique, he presented his most important thesis: hieroglyphs are partly true ideograms, which represent complete words (concepts), partly phonetic characters, which reproduce sounds, and finally partly ‘determinatives’.”[7]

In the translation of the Rosetta text, one finds the disclosure of an assembly of priests, which took place in Memphis in the year 196 A.D. The priests praise King Ptolemy Epiphanius and thank him for the benefits granted to them and their temples.

Thus, by deciphering the hieroglyphics, Champollion was able to lift the veils that covered up three thousand years of history of one of the oldest civilizations in the world.[8]

By João Pedro Serafim

[1] Cf. https://gaudiumpress.org/content/a-origem-da-escrita-parte-i-a-escrita-cuneiforme/

[2] Cf. STORIG, Hans Joachim. The adventure of languages. Translated by Cloria Paschoal de Camargo. Cloria Paschoal de Camargo. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 2003, p. 15.

[3] Cf. ibid.

[4] Cf. ibid., p. 15 and 16.

[5] Rosette is the French version of Raschid.

[6] Ibid., p. 14.

[7] Ibid, p. 18.

[8] Cf. AUDIBERT, Caroline; DE LA BRETESCHE, Geneviève. Grands personnages de l’histoire de France. Paris: Arthaud, 1990, p. 41.